Le Mal du Pays

I.

It was the summer of 19— (and that’s enough to date me) and I’d been away, already, at university for a couple of years. In those days, during breaks and weekends, I wasn’t going “home” to the mid-sized town in East Texas where I grew up; instead, I was going to Houston to stay with my maternal grandmother (qu’elle repose en paix). I saw my family often enough. There were plenty of phone calls and the emails were starting to fly back and forth while I was still getting used to writing them.

Due to a bit of luck (or perhaps a bit of wisdom), both my parents were educators (now retired), and so at that point in my life, I had been fortunate enough to have visited somewhere between 25 and 30 states in this grand ol’ union of 50. Always by car (those epic road trips, books and movies and games for endless entertainment), such travels were the highlights of our long, away-from-school, vacations.

Everything took a dramatic change in the aforementioned summer, an expected, though fully-embraced, topsy-turvy transformation.

I was smart (can we use precocious to describe a young man in his early 20s?) and had traveled more than most my age. I’d read more than most my age, too. I’d left the country many times to visit the England of Sherlock Holmes, Candide’s Europe, even Gulliver’s Lilliput. Yet, I’d never left the U.S., and I’d never traveled on a plane. I’d never even owned a passport. In the summer of 19— (feel free to hum that Bryan Adams tune, but let’s be ABSOLUTELY CLEAR, it was not, I repeat, it was not the summer of which he sings), I embarked on my first overseas journey, heading to Paris and other parts of France, as well as London.

At the airport, I was like a kid at a train station or, maybe, just like a kid at the airport. I watched plane after plane take off and land; I watched them taxi to and from the gates. Heck, I even watched my luggage conveyor into the bowels of the airport, and the glorified golf-cart-trains take said bags to the belly of the 747 beast. Everything was shiny and interesting, exciting and awe-inspiring. The nine-and-a-half hour flight would culminate in a completely new understanding of myself.

The descent into Paris started the following morning; I hadn’t slept a wink, it was just too cool to be on a plane, watching movies, eating free snacks and meals, drinking wine and champagne. I can honestly say I really don’t remember whether, as we approached the city, I was able to see la Tour Eiffel from the window,

or if the Byzantine poke of Sacré Coeur would have nudged us off course from Roissy-Charles de Gaulle.

But I do remember landing. I remember the final drop in altitude towards the runway, clouds giving way to the cool gray of morning, then the industrial gray of buildings, and finally the slate gray of airstrip. I remember, as we taxied, seeing for the first time French trucks and French buses, shuttling equipment and passengers from one adventure to the next. I remember wondering what cool things the French pilots were saying to each other, and whether I would understand them in my still-basic French. I remember the feeling of return, the feeling that I was home, unknown but welcoming.

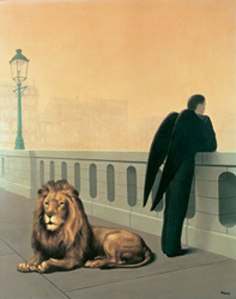

But it wasn’t just a feeling. I was home, return of the son long lost from the arms of the Iron Lady, the fils manqué finally back to Marianne, enfant adopté de la patrie (to the tune of “La Marseillaise”), but part of the family all the same. It was as if I were starting my own “Notebook of a Return to the Native Land” though it would be another year or two before I would be drawn into Césaire’s text, a poem that still mesmerizes and confounds my understanding. I found myself in the land of Voltaire, ready to be lost in the crowds of Baudelaire, wandering the street poems of Prévert. I was eager to traverse the dreamscapes of Breton, stroll the rues and the boulevards under the sun and the moon, succumb to the embrace of the Left Bank and the Right.

Between the shades of gray, the jolt of ground and the screech of tire, I knew that I was chez moi. After that arrival, plane cozied up to the gate, my torrid affair with Paris would leave the page and the pensée and be manifest in narrow streets and nightly walks, in park picnics and museum meditations. I would come to discover the self I had never known, but had always suspected. And the US would henceforth be a place I was visiting, a temporary stop on return flights to La Ville Lumière.

à suivre